Thoughts on Writing Crime Fiction

- gemoijones

- Apr 5, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 8, 2022

How far is too far for crime fiction?

Can crime fiction be accused of glorifying the dark side of life for entertainment?

The general discussion is around the issue of censorship, its role in society and how far freedom of thought and expression might be curtailed because of the perceived risk of an adverse impact on the individual or society.

Here, it’s squarely placed within the realm of literature and art. Violent films may be described as ‘pornographic’ and be suspected of inciting violence. The 1971 film ‘A Clockwork Orange’ was withdrawn by its maker Stanley Kubrick when it was suspected of that. Books have a longer history of censorship whether because they have been seen as too violent, or as deviant in social, sexual, or political terms.

As far as Crime books are concerned I undertook some research as to the naughty crime books that have been banned, for whatever reason. The result was interesting.

Even Stephen King has been known to withdraw a book (Rage) as it was believed to have incited real life copycat violent crimes.

Where individual liberty to write meets individual freedom of choice to read, then a simple instruction or warning on the book cover can, on the face of it, solve the tension point. Don’t read it if you don’t like the graphic descriptions inside or if the subject matter is not to your taste.

What about the occasions where a writer inadvertently upsets/offends a reader?. Surely, in this case the reader carries responsibility. It is clear that writers cannot cater for prejudice or unexpected sensitivities.

What if the offending bit is well buried in the book. Where it springs out on the reader, unannounced, unwelcome, and offensive/upsetting/triggering..

Reading books like this in the past, I admit having been surprised in turning the page, by graphic violence. It has upset me, as has exploitation, misogyny, racialism, homophobia, animal cruelty and this list is not exhaustive. They have, at various times, all stopped me reading a book.

But as a writer, I can only answer as an individual, not as some guardian angel for other people’s tastes.

What boundaries do I have where I can write and express myself with a measure of comfort and enjoyment?

The short answer is that I don’t stray into the same territory that upsets me as a reader.

Which leaves me still having to wrestle with the ‘crime’ issue itself. Is it intrinsically offensive?

The genre comes with its paraphernalia, including blood, cruelty, sadism, and abuse. All of a sudden, that bears disturbing similarity to my banned list.

So, what is going on here?

For several decades I worked in an occupation where I had to deal with those very same terrible issues. I was involved on frequent occasions, in an investigative and forensic role, with the fallout from criminal acts and abuse that inflicted death and injury. When I began that part of my career, the experience was traumatic, and one I had to continually try to come to terms with. Yet, I still read crime books and I have wondered about how my mind appears to distinguish between the reality and fiction of that.

Human beings are fascinated by the criminal side of their nature. What might lie beyond the light. But how close do they want to get to inspect that side? What protective walls are created in our psyche when these criminal acts are performed in fiction?

Professor Angela Gallop, the forensic scientist in her fascinating book ‘When the Dogs Don’t Bark’ recounts that in her early career, she was involved in the investigation to catch the Yorkshire Ripper. She recounts an incident where a man is arrested during that investigation but proves to be the wrong suspect. She uses this example to illustrate that in this world, ‘truth often is stranger than fiction’.

The suspect, despite all the (extremely) suspicious circumstances, was innocent, or at least innocent of the crimes in question. Professor Gallop describes the man as turning out to be a fetishist who dressed up in wig and pantaloons with a habit of setting fire to himself. The blood soaked tissues in his home, removed for analysis, proved to be stained by his own blood from his attempts to staunch his bleeding gums after he had all his teeth removed.

She reports it was the first of many 'madhouses' she would come across in her forty year career.

Truth or Reality and Fiction occupy different worlds, and comparison in my view is an invalid exercise and for some people, it is a dangerous confusion. There is much more than a thin dividing line between real crime and fictionalised crime. They occupy entirely different parts of our mind or should do.

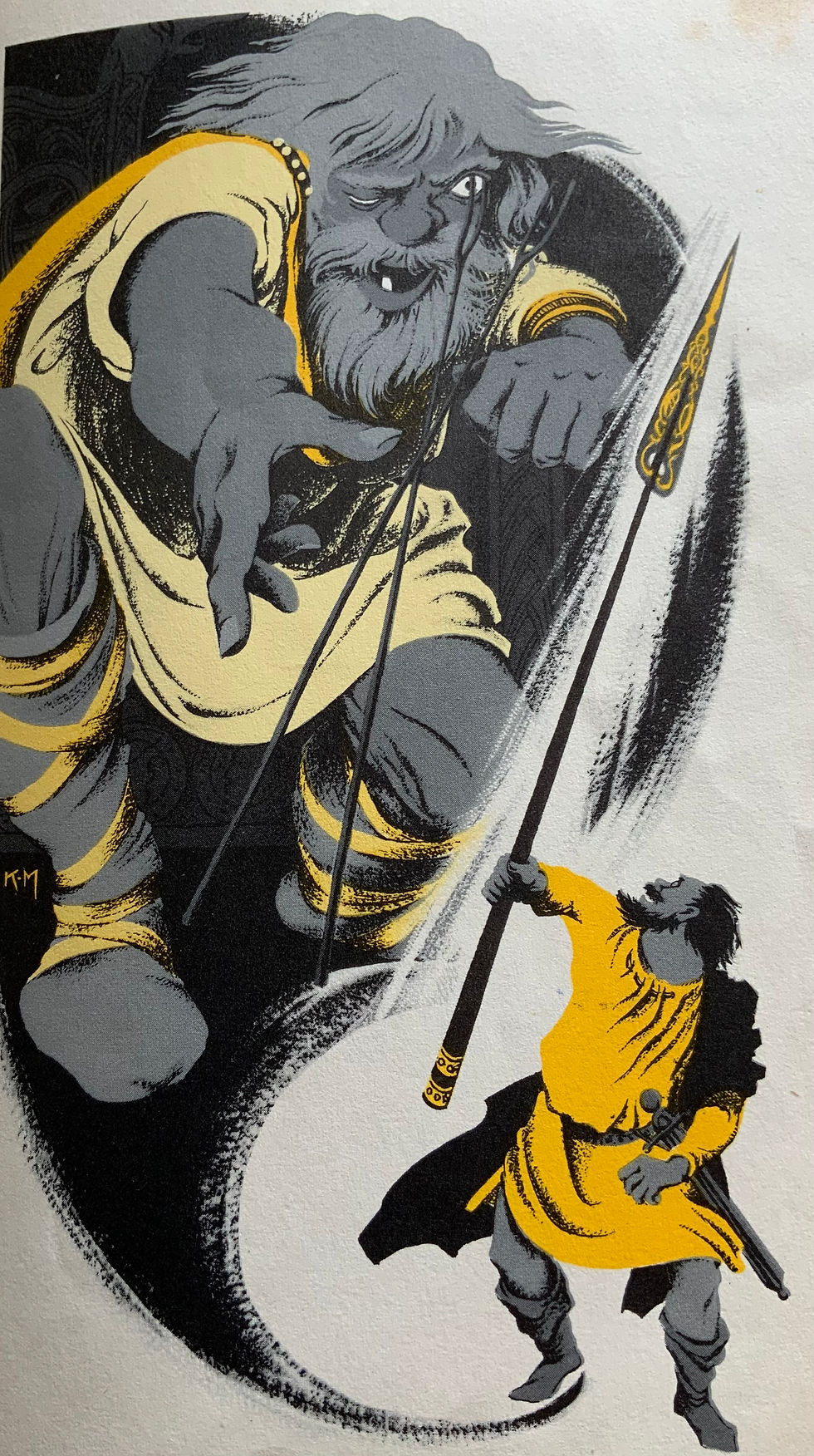

Is crime Fiction compartmentalised into the modern adult version of the 'fairy tale' section of our story brain? Fairy tales were not always directed at children. The Arabian Nights, like many old folk tales, were meant for adult consumption and brim full of death, blood, and psychopathic genies/ogres. That collection of tales contains stories of detective deduction (Ali Baba contains one of the earliest examples of that genre) as well as of murder and general criminal mayhem.

When telling a story within the circled light of the camp fire, well away from the darkness out there, there are certain rules.

Writing crime carries risk and responsibility.

Don’t write crime in such a manner that it glorifies the criminal act.

Entertain with the story, not with the crime itself.

I’m sure there are other rules.

The writer can’t be entirely responsible. Stephen King certainly had no intention of adversely influencing any reader. Perhaps the writer ideally can try and exercise judgement before putting pen to paper or a director making a film. But sometimes that’s not possible, because readers/filmgoers have responsibility too and some can’t be trusted. As a result, Kubrick withdrew The Clockwork Orange and King, his book.

If those responsible, talented, and skilled artists have found themselves in that position, then it warrants some more hard thinking. Certainly, on the part of anyone tempted to write the absolutely perfect crime in their book. You never know that some wannabe criminal genie or ogre may decide to copycat.

Comments